As a practising illustrator, my working methods have always been non-linear. I find it difficult and constricting, with any project that consists of more than one image, to work on one spread at a time. This isn’t a problem at the rough stages and I can produce the pencil sketches in a fairly linear manner once the manuscript has been given to me. It’s the part when it comes to colouring the spreads that I have to complete as a whole.

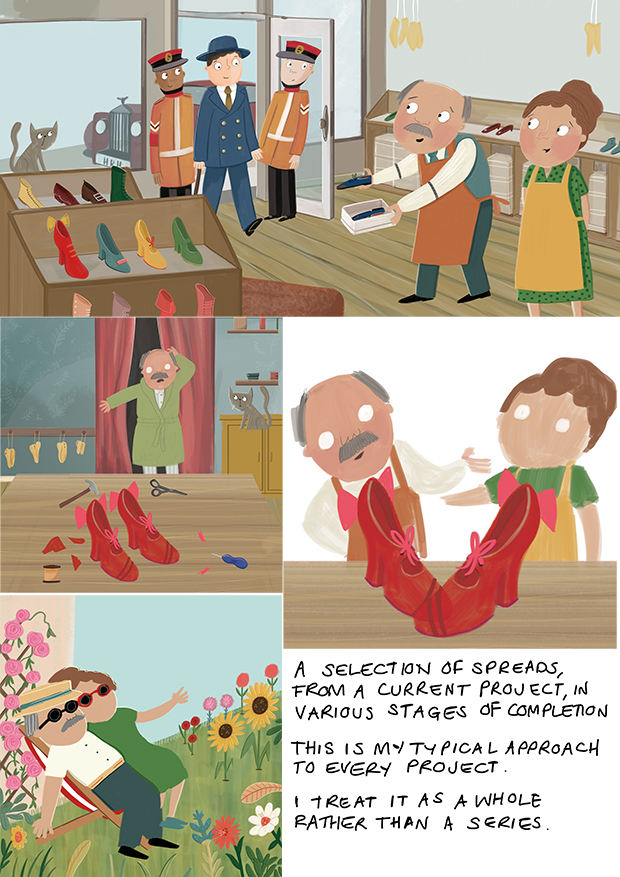

Currently I’m illustrating a re-worked version of The Elves and The Shoemaker (Miles Kelly, 2018). There are a mix of 22 double and single page spreads. I’ve started work on all of these and they will all remain in a part finished state, adding more and tweaking as I go, until I’m ready to finish them all in an order that makes sense to me, rather than the numbered page order.

This can be a sticking point for clients so I ask them if there are any spreads they need me to work on first (this is especially important around the major children’s book fairs like Frankfurt and Bologna) where publishers are often selling books and rights on the strength of one or two spreads and a cover. This is always the most difficult part of the process for me as I find it difficult to make sense of why I’m starting at that particular point, finishing the spread and then starting on the others separately as if they’re part of a different set.

I think this method comes from the storymaker aspect of what I do. I’ve spoken to other author/illustrators who often formulate a story and the illustrations at the same time. This process usually starts with a sketch of a character or an idea for a scene and then we build out from the middle or the end and rearrange the parts of the story until they’re in the most satisfactory order.

I can, and have, worked in a linear way when clients have requested it. I don’t feel that I produce my best work by doing this as I lose the freedom and ability to slowly layer and build up each spread. This results in me feeling stifled and just wanting to get the work done which can lead to the work losing its character. An experienced illustrator told me, when I was right at the start of my career, to always remember “You’re not a sausage factory”. As funny as that sounds, it really resonates, especially now that I too have some experience behind me. I don’t want to keep producing the same thing on demand every day, with the same ingredients, in the same way.

Looking deeper into this non-linearity, it seems to be the way I approach things in general. To avoid an overly digital look to my work, I like to build colour and texture in layers, juxtaposing soft brush textures and hard edges over a contrasting underpainting. I do appreciate that thought processes and actions usually have a beginning and end, but I definitely like to take a more holistic approach.

Peter Brown’s working methods are very similar to mine except he plans his spreads in order of difficulty. I don’t account for this ranking system when I’m working in colour but I do make sure everything is worked up to a similar level before going to final art on any spread.

I’m reflecting on this here as this is something fundamental that underpins my work. Efforts to change this, or workaround it, always leave me with a deep sense of dissatisfaction. Although illustration is a commercial discipline, this is one of my sources of freedom during the creative process.

SEVEN IMPOSSIBLE THINGS (2010), Seven Things Over Breakfast With Peter Brown. [Online] Available at: blaine.org/sevenimpossiblethings/?p=1920

Thank you for talking about your processes – the things you find challenging, the freedoms you need to have to do your best work, and the things you have discovered work best for you. I have generally found that I work best at anything when I can abandon the rule book at an early stage, which can be awkward, when trying to function within systems. However, there is always a rationale behind the ways different people work and it’s best to find ways of harnessing rather then resisting that.